Cummins Turbo Technologies and hydrogen in the UK: a report by T&BB

By Bradley Osborne - 11th July 2023

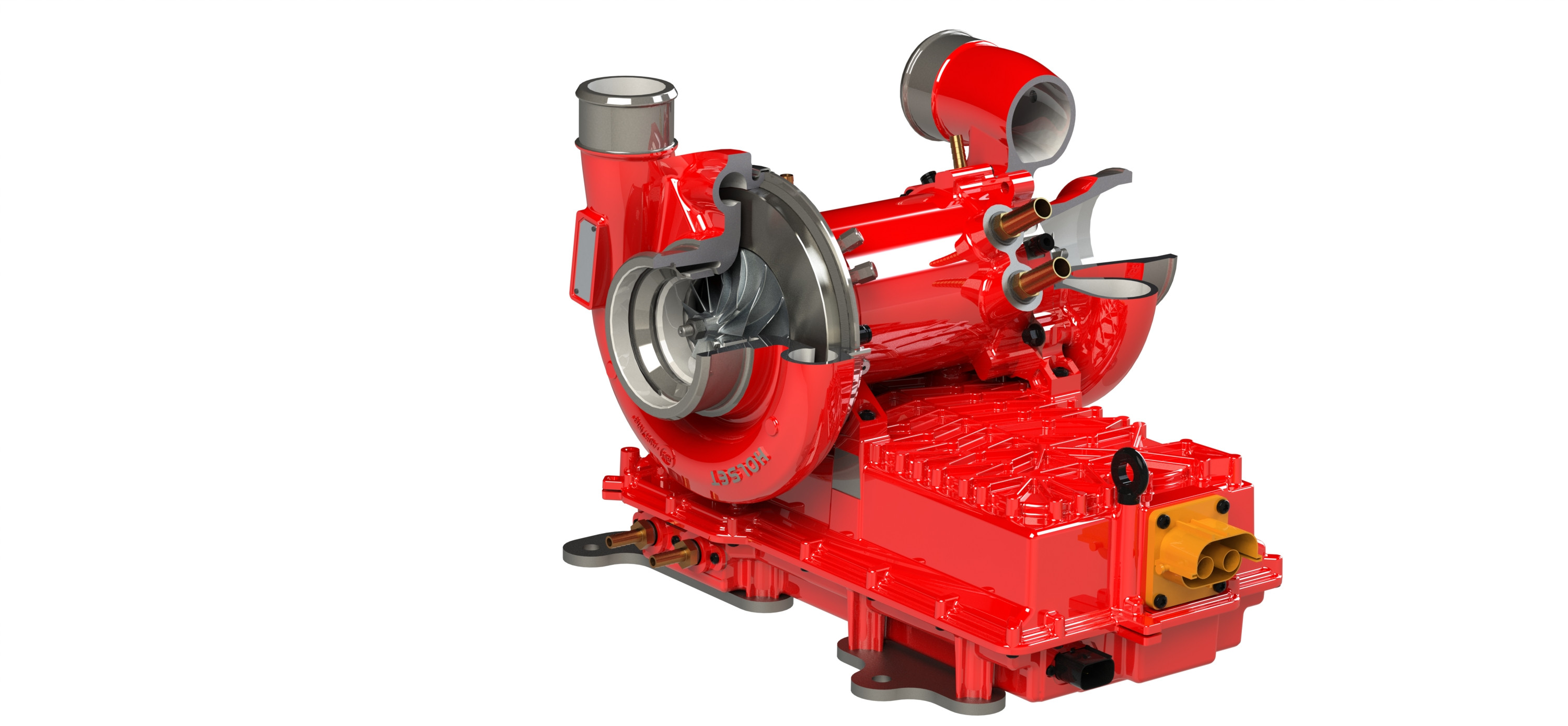

Turbo range at Cummins Turbo Technologies in Huddersfield

UK – We hear and read a lot about electric vehicles and the components required to make them work (motors, batteries, fuel cells). We hear far less from the manufacturers of components which are required to make combustion engine vehicles work. They are by no means near to disappearing in a puff of smoke: they continue to diligently make and invest in their products and will continue to do so for far longer than some would care to admit. But even if the internal combustion engine is fated to end up in the scrapheap, its subsidiary components – the turbocharger, for instance – might have some surprising applications in the brave new world of electric vehicles.

Cummins Inc is not prepared to relegate anything yet to history’s scrapheap. At the last IAA in Hanover, the American company presented a series of new gas engines and – a first for the company – an internal combustion engine powered by hydrogen. It is also going all in on electric powertrains. To acquire the technology required for this, it took over Siemens and Meritor for their electric drive systems and Hydrogenics for its fuel cells. These are now grouped under a new division called ‘Accelera’, which will also be responsible for making electrolysers for green hydrogen production.

Visiting the Cummins Turbo Technologies facility in Huddersfield, UK showed me what all of this means beyond the slick corporate presentations. It means that Cummins’ turbochargers will continue to be absolutely necessary for its combustion engine products well into the future. It also means that its turbo technology will gain a new lease of life in its fuel cell drive systems. As such, Cummins has invested USD25m in the Huddersfield plant, expanding its testing capabilities and refurbishing the production facility.1

All of this greatly depends, however, on external factors. Recent developments in government policy in North America and in Europe suggest that scaled up production of “green” hydrogen is on the way. In the UK alone, there are two major projects for hydrogen production ongoing and fifteen more prospective ones. This was told to delegates at a recent conference in London, ‘Hydrogen for Life’, held between 14-15 June at the Science Museum. Speakers included representatives from Cummins and Bosch, and both companies had promotional stands outlining their respective contributions to a burgeoning “hydrogen economy”. The mood at the conference was upbeat. However, hydrogen’s application as a fuel for transportation was sidelined somewhat. One speaker admitted that the battle between batteries and hydrogen in the passenger car and light van segments was “already over”, with the former coming out on top. If hydrogen is to have a role in decarbonising road transport, it will be in the heavier vehicles: the long-haul truck and the coach, as well as agricultural and construction machinery. This is the niche in which Cummins’ hydrogen products have the potential to thrive.

'Project Trident' e-turbo

Turbo technologies and hydrogen drivelines

The history of turbocharger design and manufacture in Huddersfield goes back to 1952, with the incorporation of ‘Holset Engineering Co’. The company was purchased by Cummins in 1973, and in 2006, it was renamed as Cummins Turbo Technologies – though its turbocharger products still carry the Holset name. Since the rechristening under its own name, Cummins has put the subsidiary to work on making its products more fuel efficient to ensure compliance with increasingly stringent emissions regulation. Since 2013, the engineers at Huddersfield have achieved a 12% improvement in the efficiency of the wastegate, the valve controlling the flow of exhaust gases to the turbine. Moreover, the efficiency of Cummins’ variable-geometry turbocharger – which alters the effective aspect ratio to optimise performance in varying operating conditions – has been improved by 9% in the same timespan.

Future emissions regulation remains a primary focus of research and development at Cummins. The people at Huddersfield said that Cummins’ acquisition of engine-braking specialist Jacobs Vehicle Systems last year is helping their R&D considerably. Bringing together various aspects of engine design and development under one roof allows Cummins engineers to take a more holistic, or systems-based engineering approach to the problem of emissions reduction. But there are other focuses, too, such as thermal management, better use of “pulse energy”, duty cycle-based development, and fuel agnostic capability.

The last focus ties in with the subject of hydrogen. The engineers at Huddersfield are working on turbo prototypes which will work effectively with the spark-ignited hydrogen engine currently under development across the pond. They are working with partners in ‘Project Brunel’, which is funded by the Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC).2 Three thousand test hours have already been completed. So far, Cummins Turbo Technologies is finding that it may need a larger turbocharger to bring the hydrogen engine up to the same performance levels as a diesel equivalent. Turbochargers for future hydrogen combustion vehicles may favour a fixed-geometry design and a twin-turbo configuration. Moreover, they may use motor-driven compressors to replace some of the exhaust gas recirculation.

At the same time, the engineers at Huddersfield are working on turbo technologies for fuel cell electric vehicles. Optimising the supply of air in a fuel cell drive system can bring similar benefits to a turbocharger in a conventional engine: increased power output, increased power density, and increased system efficiency. One way of achieving these results is to employ an electric compressor; for a 250-kW fuel cell stack, a 70-kW compressor would be required. However, Cummins Turbo Technologies is looking into replacing the compressor with a 45-kW e-turbo instead. With an e-turbo, there is the potential to recover up to 30% of the waste energy, while up to 40% of the required compressor work can be recovered by the turbine (equivalent to 25 kW additional to the 45-kW motor). The company believes it can achieve an 8% fuel efficiency improvement on a conventional fuel cell system with e-compressor. Its hypotheses are the subject of another project, also APC-funded – the GBP20m ‘Trident Project’.

From 'Hydrogen for Life' conference in London

The UK’s burgeoning hydrogen economy

While the engineers at Huddersfield work on turbo technologies for hydrogen-fuelled drivelines, the parent company is making plans to establish a hydrogen value chain for road transport, comprising fuel production and complete powertrains for heavy-duty vehicles. Cummins aims to begin producing hydrogen engines at scale by 2027. As for fuel cell drive systems, though these are already being produced at low volumes, it won’t be until the end of the decade before Cummins begins mass production.

Delegates at the Hydrogen for Life conference were told that the UK is already making great strides towards establishing green hydrogen production at scale. Two major projects – the Teeside hydrogen project in the northeast of England and ‘HyNet’ in the northwest – are already underway. But there were warnings that the government could fail to come through with the funds required to finance ongoing and prospective hydrogen projects. Right now, Parliament is debating whether or not investments in the hydrogen economy should be paid for in part by the taxpayer, through a levy on household energy bills. Attendees at the conference were naturally keen to see as much money as possible committed to scaling up hydrogen, as soon as possible. The UK government’s target is for 10 GW of hydrogen production – of which half must be electrolytic – by 2030.

Alexey Ustinov, Vice President for Electrolysers within Cummins’ Accelera business, pointed to the example set by the United States, which is committing massive funds towards hydrogen through its Inflation Reduction Act. Ustinov called this act a “game changer” for its tax credits of up to three dollars for every kilogram of green hydrogen produced. Jaymes Mackay, Energy and Mobility Strategy Director at KPMG, said the UK has “lost twelve months” on the U.S., with the act spurring investors in the hydrogen economy to shift their attention from the UK to the USA.

The future looks bright for Cummins’ hydrogen business, whether the support comes from the UK or elsewhere. Whether or not the hydrogen driveline products will be carried along in the swell is another matter. Cummins Turbo Technologies stressed that decarbonisation is a “growth opportunity” for the business, a chance to develop new products for air handling and turbocharging in hydrogen fuel cells and engines. However, Cummins will need governments in the UK and abroad to keep as many options on the table as possible. That means they should stop legislating against technologies (i.e., in favour of battery electric) and start embracing low carbon options such as hydrogen combustion, which uses many of the components and technical capabilities already in place in Huddersfield and other sites. It also means putting money towards scaling up hydrogen production and distribution, so fleets have ready access to fuel. As one speaker at the conference put it, while the last year has seen a lot of progress in the development of a UK hydrogen economy, the future of that economy has never felt so precarious.

1 See the separate article in this issue about Cummins’ investments in Huddersfield.

T&BB would like to thank Duncan Engeham, Research and Development Director for Cummins in Europe, and the people at Cummins Turbo Technologies for the information presented in this article.

.jpg?w=400&h=225&fit=crop)