The EU Battery Passport and Its Implications for the Commercial Vehicle Sector

By Luke Willetts - 29th July 2025

EU Battery Passport

Germany – As the European Union intensifies its transition to net-zero mobility, attention is increasingly turning to the batteries powering that shift, not just in terms of performance (duty cycles), but also regarding how they are produced, where their raw materials come from, and how they are handled at end-of-life. In a landmark regulatory move, the EU has finalised plans to introduce the world’s first large-scale “Battery Passport” scheme. Starting from 18 February 2027, batteries sold within the European Union, beginning with those used in electric trucks, buses, industrial machinery, and light commercial vehicles, will be required to carry a digital passport that provides comprehensive information on their lifecycle and sustainability credentials.

This initiative is part of the broader EU Battery Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 and represents a decisive step toward a “circular battery economy”. It is also a major inflexion point for the global battery industry, with implications extending far beyond Europe. For the commercial vehicle sector, it marks a shift in how value is defined, beyond performance metrics like voltage and cycle life, to include carbon emissions, regulatory compliance, and material circularity.

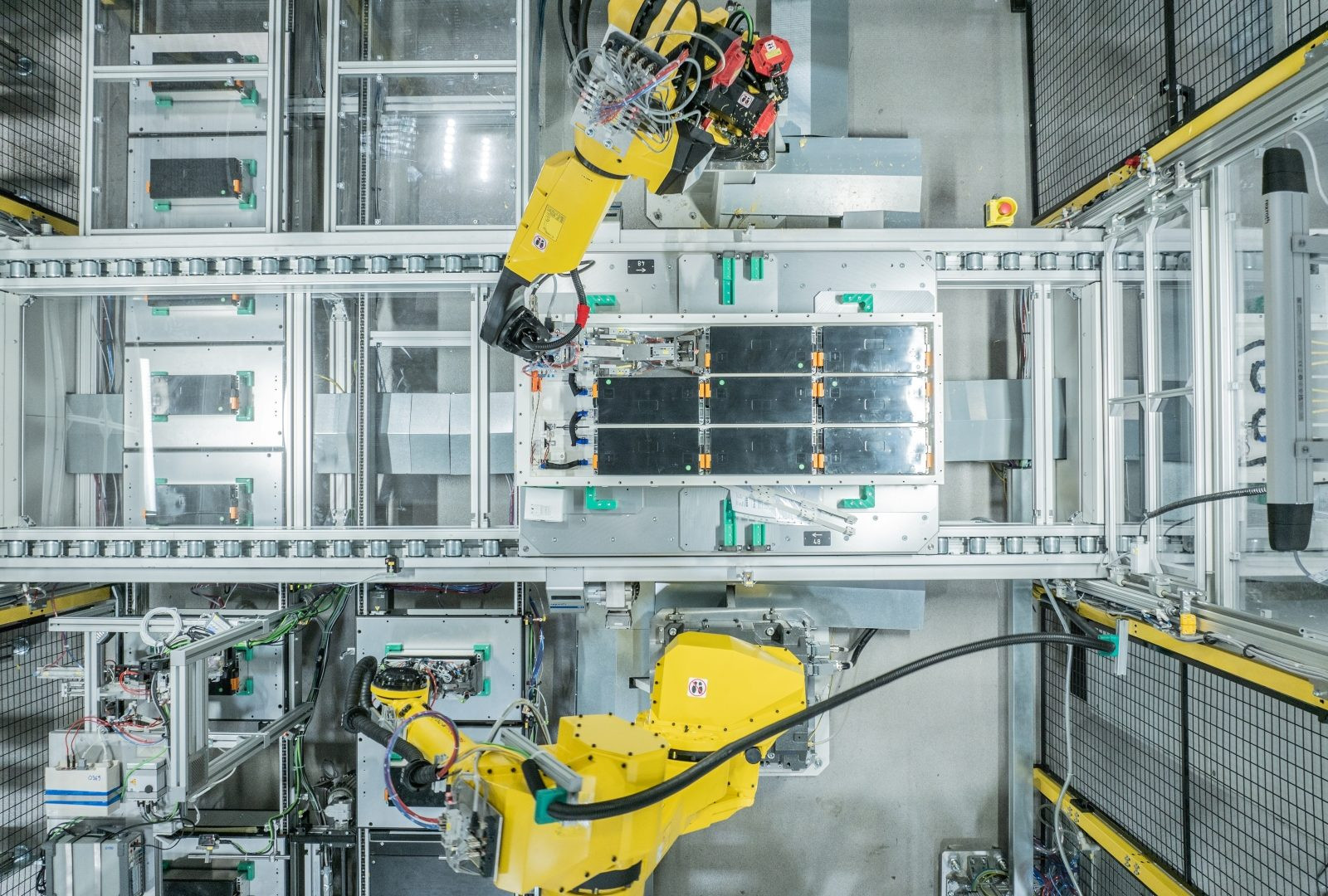

BorgWarner LFP flat pack

What is the Battery Passport?

At its core, the Battery Passport is a digital record accessible through a QR code printed directly on the battery casing. This QR code links to a secure registry managed by an EU-recognised digital platform, where verified information is stored and maintained. The passport contains key data about the battery’s origin, chemical composition, carbon footprint, recycled material content, and performance history. Particular emphasis is placed on the traceability of critical raw materials, such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel minerals, which are often associated with geopolitical risk and environmental or ethical concerns regarding labour conditions at mines and factories.

The passport is being developed in cooperation with OEMs, battery producers, digital solution providers, and independent certification bodies. Its purpose is to make every battery “trackable from cradle to grave” and potentially beyond, into second-life use. It is also the first tangible implementation of the EU’s wider Digital Product Passport strategy, a key element of the European Green Deal.

Why is the EU introducing it?

The Battery Passport addresses both strategic geopolitical (competition) and ideological (climate change) imperatives. According to the European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform, a joint initiative by the European Commission and the European Economic and Social Committee, strategically, it responds to the need for “secure and standardised data in a global battery supply chain that is often fragmented and opaque”. This is particularly true, given the dominance of non-European players in rare earth material mining and processing. Ideologically, it reflects the EU’s commitment to “climate action, social responsibility, and environmental stewardship” by promoting “sustainable practices”.

European Commission, Brussels

It also aims to drive the development of a circular battery economy. By making accurate information on battery durability, health status, and recoverable materials publicly available, the regulation encourages second-life applications and more efficient recycling. Several major OEMs, including Daimler Buses and MAN Truck & Bus, have already initiated programmes to repurpose used EV batteries for stationary energy storage. These efforts will be strengthened by the centrally housed data provided through the passport system.

How will it work?

Beginning in 2027, manufacturers of batteries with a capacity greater than 2 kilowatt-hours, relevant for most commercial vehicle applications, must generate a digital passport for each unit placed on the EU market. This requirement applies equally to batteries produced within the EU and to those imported from abroad. Each passport will be linked to a centralised, cloud-based database, accessible via a QR code physically attached to the battery. Manufacturers will be responsible for uploading and maintaining data covering the battery’s material content, supply chain origin, carbon emissions throughout production, recyclability, and real-time performance metrics.

Recycling facilities will also contribute to the data trail by recording dismantling processes and recovery rates once the battery reaches end-of-life. The system thus creates a comprehensive cradle-to-grave audit trail that captures environmental, technical, and economic attributes. The EU is also implementing rules that require independent verification of certain key data points, particularly those related to carbon footprint disclosures. According to the European Commission (EC), importers, distributors and OEMs that integrate these batteries into vehicles will share responsibility for compliance.

Who will enforce it?

“National authorities in each EU Member State (e.g. environmental agencies, customs, product safety regulators) are charged with market surveillance and enforcement”, say the EC. These authorities will be supported by digital validation tools and procedural protocols to ensure consistency. Batteries that do not comply with the passport requirements will be denied CE marking (Conformité Européenne, European Conformity) and, therefore, prohibited from legal sale within the EU. Enforcement will be both proactive and reactive. Regulators may request to see a battery’s digital passport during product registration, vehicle type approval processes, or customs inspections.

“The strength of the regulation lies in its harmonised application across member states. Whether a battery is manufactured in France, Poland, China, or South Korea, it will be subject to the same data reporting, audit verification, and traceability standards”. These are the policy guidelines outlined by the EC.

Chinese vs European battery manufacturers

Although the regulation is origin-neutral, the implementation burden may fall unevenly across global suppliers. Chinese battery manufacturers such as CATL and BYD, which currently dominate the global market through scale and cost advantages, may find it more difficult to comply with the EU’s rigorous transparency and verification requirements. These companies operate in regions where environmental and labour oversight differs markedly from EU expectations, and they may lack local infrastructure or partnerships to fulfil the passport’s demands.

By contrast, European battery makers such as Impact Clean Power Technology, Forsee Power and BorgWarner (formerly Akasol), have built their business models around sustainability and traceability. For them, the Battery Passport presents a strategic opportunity to be more competitive in the European market. The regulation should offer a commercial edge to those who are already aligned with the EU’s priorities, particularly as fleet operators and public buyers become more focused on decarbonisation and ESG performance.

Impact Clean Power Technology battery plant in Warsaw

In the short term, the compliance requirements will increase operational costs for all battery producers. These costs stem largely from the need for new digital infrastructure, lifecycle audits, and data management systems. However, in the medium to long term, European companies should benefit. The passport creates new forms of value by institutionalising transparency. Batteries that are demonstrably low-carbon, responsibly sourced, and easy to recycle may become more attractive to customers (artificially), especially in sectors governed by public procurement rules or green investment criteria. This can be seen as another form of European trade protectionism, or in the words of U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent, “a non-tariff barrier”.

The Europeans would counter this claim by saying that the availability of consistent, verified data across the supply chain can reduce friction in resale, repurposing, and recycling. This, in time, increases battery lifetimes, lowers their costs for fleet operators and increases the residual value of battery-equipped vehicles.

An IVECO E-WAY electric bus, a European OEM, with Forsee Power batteries

The circular economy

Perhaps the most significant long-term impact of the Battery Passport lies in its potential to support the EU’s strategic autonomy. By tracking material flows from extraction to recycling, the regulation ensures that valuable resources are not lost at end-of-life but are instead recovered and reprocessed within the EU. The regulation sets ambitious recovery targets for critical materials, such as 90% for cobalt, nickel, and copper, and between 50% and 80% for lithium by 2030.

This closed-loop approach not only reduces Europe’s dependence on external supply chains but also supports domestic job creation, investment in recycling infrastructure, and innovation in materials science. It aligns with broader EU goals to strengthen sovereignty in key industrial sectors.

What isn’t covered in the Battery Passport?

The Battery Passport will provide detailed information on a range of lifecycle metrics. These include the battery’s material composition, recycled content, carbon emissions during production (including the energy mix used), projected lifespan, capacity retention, and real-time state-of-health tracking. It will also include due diligence reports on the sourcing of critical minerals and flag any connections to conflict zones or human rights concerns.

Mine in the Congo

However, the passport will not include proprietary intellectual property such as specific cell chemistries or manufacturer trade secrets. Nor will it collect personal data or consumer usage information. Its function is strictly industrial. According to the EC, “it is a traceability tool for regulators, manufacturers, and supply chain participants, not a surveillance device”.

What will be the impact on battery prices and electric commercial vehicles?

The cost of complying with the passport framework is expected to raise battery prices by an estimated two to five percent, according to the EC. For large-format batteries used in commercial vehicles, this could translate into several hundred euros per unit. These costs will likely be passed along the supply chain, at least during the initial rollout phase. As batteries currently account for between 30% and 40% of the total cost of an electric truck or bus, this increase should have a noticeable impact on the final sale price of electric commercial vehicles.

Nevertheless, over the longer term, the passport may help drive down total lifecycle costs. Improved recycling and reuse, along with more accurate performance and degradation data, will enable better asset management. OEMs and fleet operators may benefit from optimised maintenance cycles and fewer unexpected failures, potentially enhancing overall return on investment.

Looking Ahead

The EU Battery Passport represents a bold step in the evolution of sustainable transport regulation. For commercial vehicle stakeholders, it offers both a compliance challenge and a strategic opportunity. While implementation will require investment in new systems and processes, the long-term benefits (greater supply chain visibility, lower lifecycle costs, improved recyclability and enhanced customer confidence) could reshape the competitive landscape.

When traceability and transparency become as vital to buyers as range, torque, and payload, European battery manufacturers are likely to see their market position strengthen against Eastern competitors.

CATL factory in Guangdong

Our feature article on BorgWarner’s battery plant tour in Darmstadt is now live – click here.

You can also read our coverage of Impact Clean Power Technology’s Gigafactory X opening – click here.