“Canada’s Silicon Valley”: A study of automotive tech firms in the Toronto-Waterloo corridor

By Bradley Osborne - 21st March 2023

Skyline of Toronto, Ontario

Part of a series of features on the tech industry and its impact on commercial vehicles, this piece looks at established firms and start-ups based around Toronto and in the Regional Municipality of Waterloo, both situated in southern Ontario, Canada.

Canada – In the 2000s, the word “blackberry” became synonymous with a new kind of phone: the smartphone, a multimedia device capable of more than just taking calls and sending texts. Nowadays, the smartphone is ubiquitous in many places across the world and is a symbol as well as a product of the global economy in which the majority of us live and work. Most phones made today are Apple or Android; none are “blackberries”. But BlackBerry Ltd – a tech company residing in the city of Waterloo in the Canadian province of Ontario – was a pioneer in the design of early smartphone devices and enjoyed a great deal of success before it was edged out of the market by fierce competition from the iPhone and the myriad Android phones towards the end of the 2000s.

The company’s old management departed in 2012, and Toronto-based investor and majority shareholder Fairfax Financial pumped USD1bn into the failing company and installed John S Chen as CEO to turn its fortunes around. Chen was prepared to do whatever it would take to improve the company’s performance, even if that meant abandoning BlackBerry’s stock-in-trade, the smartphone. An article published on 4 November 2013 by The Globe and Mail described Chen as a “turnaround artist”, somebody uniquely capable of reforming a company otherwise destined for total collapse. In this article, Sean Silcoff writes:

Mr. Chen again has his eye on the future. He notes that BlackBerry also has software developed by its QNX division that enables machines to communicate with each other wirelessly, such as systems in automobiles that can interact with dealerships.

Here Chen was referring to an idea which we now hear about all the time: the “Internet of Things”, or machine-to-machine communication between a dizzying array of different objects which were previously analogue devices. Vehicles that communicate with and transfer data to remote servers and GNSS are the norm today in the developed world, and in the future they will be able to interact with infrastructure such as traffic lights and road signs.

In transitioning away from the phone market, BlackBerry relied heavily on QNX Software Systems, a company which it had originally acquired in 2010 to develop an operating system (OS) for its smartphones. When Chen took over, he set QNX to work on an OS for embedded systems applications, such as telematics, infotainment and navigation for vehicles. BlackBerry now claims that the ‘QNX’ operating system is used in more than 215 million vehicles around the world. This is quite an achievement for a company which, only a decade ago, had no interest whatsoever in automotives. The success is attributable, in part, to Chen, who realised early on that, while the smartphone market was closed to BlackBerry, the market for vehicle software was only just getting started.

More recently, BlackBerry has targeted industry concerns about cybersecurity. On its website, it states that it helps OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers to design and develop “high-performance, safe, secure and reliable software for traditional ECUs, as well as next-generation ECUs and domain controllers”. In the past couple of years, the company has published two white papers, one on software in electric vehicles and the other on the somewhat nebulous concept of the “software-defined vehicle”. And in 2021, it appointed Mattias Eriksson of Dutch automotive GPS firm Here Technologies as President of its Internet of Things business unit. The erstwhile developer of smartphones has now pitched its flag firmly in the automotive software space and is prepared to stay there.

BlackBerry’s story is not only about the growing market for digital products and services in the automotive industry. It is also the story of a particular time and place: of southern Ontario from the 1990s onwards, a fledgling hub for established tech firms and start-ups alike. BlackBerry’s founders, Mike Lazaridis and Douglas Fregin, started the company in 1984 and were engineering graduates from the universities of Waterloo and Windsor, respectively. Similarly, QNX was founded by former students, Gordon Bell and Dan Dodge, from the University of Waterloo. These individuals did not set out with the intention of working with vehicles, but it has been the fate of their companies to end up doing so, and multiple firms with an explicit focus on automotives have since then sprung up in the vicinity.

The story of the Toronto-Waterloo ‘corridor’

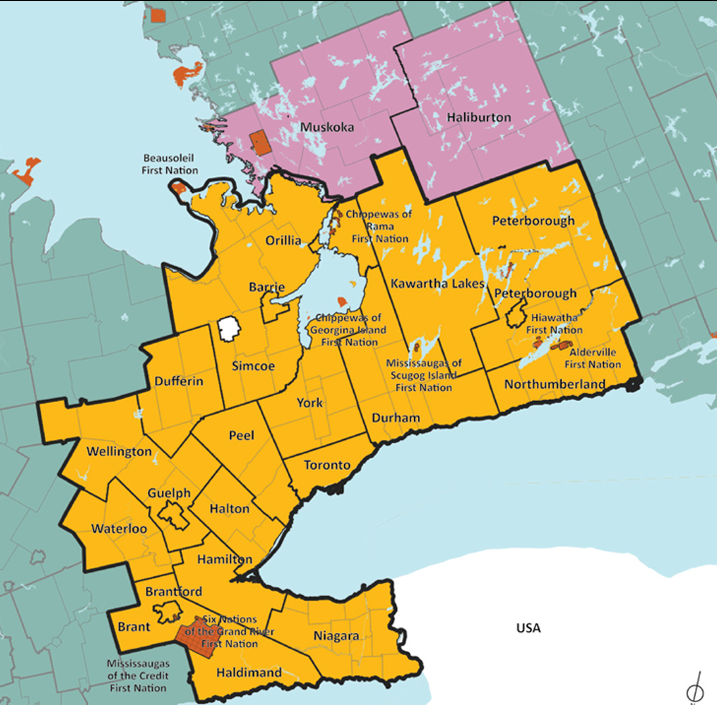

This article concerns an area of southern Ontario nicknamed the ‘Golden Horseshoe’ and its hinterland. Centred on the city of Toronto, itself the fourth most populous city in North America, the Golden Horseshoe is the most densely populated and industrialised region in Canada. To the west of the Greater Toronto Area is the Regional Municipality of Waterloo, a metropolitan area consisting mainly of the three cities of Waterloo, Kitchener and Cambridge. Within the Toronto region itself, the cities of Markham and Richmond Hill are key tech hubs.

Ontario's 'Golden Horseshoe'

A report released by McKinsey & Company in 2016 grouped these places into a single area which it called the ‘Toronto-Waterloo Innovation Corridor’ – an area which, McKinsey concludes, has the potential to become one of the world’s “top innovation ecosystems”. As of 2016, the Toronto-Waterloo corridor was home to more than 15,000 “high-tech companies” (broadly speaking, companies involved in cutting-edge product design and manufacture) employing over 205,000 workers. A 2022 posting1 by the Waterloo Region Economic Development Corporation adopted the ‘Toronto-Waterloo Corridor’ moniker and counted more than 300,000 workers employed in high tech industries, roughly two-thirds of whom are software programmers and developers. The Waterloo EDC also categorised more than 15,000 companies as “high tech”, of which over a third are start-ups. McKinsey estimated that the equity value of the corridor’s tech companies totalled more than USD14bn. While this is dwarfed by the USD411bn figure estimated for Silicon Valley, it makes the region into the undisputed tech leader in Canada.

Within the corridor, there is some competition between the cities over the status of Canada’s tech capital. The local authority of Markham promoted the city as “Canada’s High-Tech Capital” in an economic development marketing campaign in 1997. As of 2010, companies such as IBM, HP, Philips and Motorola had offices there, suggesting that the campaign met with some success. But an article published in business magazine Inc. in 2015 argued that the city of Waterloo, not Markham, was Canada’s answer to Silicon Valley. In that article, Zoe Henry states that Waterloo has the “second-highest density of startups in the world” – a claim seconded by McKinsey in its report. The neighbouring city of Kitchener is home to offices owned by Google.

The tech industry in the corridor draws its new recruits primarily from local universities. McKinsey noted that the University of Toronto and McMaster University were ranked in the top 25 and the top 100 universities in the world in 2016 respectively, and it says that the University of Waterloo – which gave birth to BlackBerry and QNX – is the top university in Canada for producing venture-capital-backed student businesses. The University of Waterloo offers a programme called ‘Velocity Garage’ which supports students in developing companies through their early stages. Both Velocity Garage and another start-up incubator, called ‘Communitech’, are based in the city of Kitchener. Henry reported that between 2010 and 2015, the government of Ontario had donated CAD25m to Communitech. However, Henry also quotes an executive of San Francisco-based venture fund, SV Angel, who said: “If you ask around Silicon Valley, all the top companies will have had an intern from Waterloo, so that's how they know about the region;” which suggests that a fair number of graduates are poached by the top Californian firms.

More importantly, the Toronto-Waterloo corridor is not only home to a thriving tech sector; it is also a keystone in the Canadian automotive industry. In 2010, the Greater Toronto Area had six vehicle assembly plants – primarily for passenger cars – owned by General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. In 1988, Toyota opened a plant in Cambridge and remains that city’s largest employer. Consequently, the corridor is also a hub for other manufacturers, making automotive components and heavy machinery. Moreover, the manufacturing hub of Detroit just across the border from southern Ontario. Tech firms based in the corridor do not have very far to go if they are looking for customers in the automotive industry.

Connections between Waterloo and major cities; Source - WaterlooEDC

Some companies based in the Toronto-Waterloo corridor

On 24 June 2021, CBC reported that the University of Waterloo was preparing to launch an autonomous shuttle bus service by the autumn of the same year. The ‘WATonoBus’ now runs on the ring road surrounding the university campus, transporting students between five stops on a 2.7-kilometre route. Companies which worked on the bus include French firms EasyMile and SBG Systems, Chinese firm RoboSense, and Trimble Applanix, a firm which was founded in 1990 in Markham and is now based in Richmond Hill (also within the Greater Toronto Area).

Applanix, a subsidiary of diversified tech company Trimble Inc of Westminster, Colorado, USA2 since 2003, now has offices in Houston, Texas, in Portland, Oregon, in Falmouth, Massachusetts, and abroad in the UK, Germany, France, Italy, China, and Hong Kong. Its primary selling point, a “position and orientation system” for mobile mapping applications, has largely been used by land and marine surveyors. However, in 2018, Applanix moved into autonomous vehicle development, realising that its mapping technology could benefit self-driving vehicles with a poor or non-existent connection to GNSS (global navigation satellite system). Trucks which have to transport material in and out of mines, for example, or indeed any vehicle which regularly travels underground, need to be able to navigate by means other than GPS. Applanix’s product works with a variety of cameras, lidars, radars, and other perception systems, and is offered as a development kit to software developers and as a production kit to vehicle OEMs.

In February, T&BB reported that Volvo had invested an undisclosed sum in another Canadian firm involved in autonomous driving – Waabi Innovation Inc, a start-up based near downtown Toronto. Founded in 2021, Waabi has developed its self-driving software using its own simulation program, called ‘Waabi World’. This program is characterised by the company as a “school” for self-driving vehicles: it provides a set of driving scenarios to actively teach and assess AI drivers. Through machine learning, autonomous driving software can be “taught” by these simulated scenarios and adjust its own code to improve its handling of real situations on the road. More recently, Waabi began integrating its ‘Waabi Driver’ technology into trucks to make them into autonomous vehicles.

T&BB also reported last year that Oshkosh subsidiary McNeilus Truck and Manufacturing Inc had acquired ‘CartSeeker’, an AI product for automating curb-side waste collection. The AI-based recognition technology can automatically identify waste bins and directs operation of the truck’s robotic lift arm without input from the joystick. It was first demonstrated in a side loader truck by McNeilus at the Waste Expo in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA in June 2021. The firm which developed the technology is Eagle Vision Systems Inc, founded nearly a decade ago in Kitchener.

Perhaps the most well-known name among Canadian tech firms working in the CV industry is Geotab Inc, which was founded in 2000 in the town of Oakville within the Greater Toronto Area. Today, Geotab also has offices in Kitchener, as well as in Shenzhen (China), Singapore, and Adelaide (Australia). Beginning as a manufacturer of telematics hardware, Geotab launched a software platform in 2010 called “MyGeotab”, through which customers can use third-party applications acquired through the online “Geotab Marketplace”. These applications provide a variety of data-driven services to fleets, and numerous programmers at Geotab are dedicated to coming up with more and more new apps.

We perhaps know more about Geotab’s work culture than any other tech firm working in the automotive industry. According to its “Corporate Profile 2020”, Geotab said it had implemented “many progressive initiatives”, such as incentives for employees and team building activities, with the aim of improving “employee satisfaction and health”. Geotab staff are reportedly provided with “ergonomic workstations, breakfast, Friday lunch and snacks, a games room, nap pod, and subsidized fitness membership”. It is hard to imagine workers on a vehicle assembly line being treated like this, but such workplace perks are commonplace in the tech industry.

In August 2022, Geotab announced that more than 3 million commercial vehicles are now connected to its software platform across 163 countries. It has worked with various OEMs, including Navistar, Cummins, Volvo, Allison Transmission, and Continental. Other digital service providers to fleets, such as MacroPoint LLC of Waterloo and Fleet Complete of Toronto, have not enjoyed quite the same level of success as Geotab but have nevertheless benefited from the growing number of connected vehicles. In its Corporate Profile, Geotab tracks this growth back to a single technological development:

In the late 1990s, a significant milestone occurred in GPS technology that would change the way business was done and set the stage for Geotab. The range of accuracy for a GPS location went from 100m to 10m. This leap in technology and precision meant that GPS suddenly became a viable source of data for businesses.

Uptown Waterloo, Ontario

Affordances and challenges of the Toronto-Waterloo corridor

McKinsey lists the following as factors behind a successful tech industry in any given area:

The presence of world-class academic and research centres; a large, high-quality talent pool; access to capital; connective infrastructure and community; high standards of living; access to early adopters or receptive markets.

As we have seen, the Toronto-Waterloo corridor is well-served for institutions of research and higher education which foster tech entrepreneurship. A 300,000 plus talent pool is also nothing to sniff at, and the area is ideally situated between the cities of the Great Lakes and the Atlantic seaboard. According to ‘Invest Toronto’, the city of Toronto has been ranked as the fourth most liveable in the world; and McKinsey points out its strong financial sector that “welcomes innovation”. As we pointed out above, the automotive manufacturing base in the corridor is considerable and longstanding.

Though the area has distinct advantages, McKinsey warned that some of these were not being enjoyed to their full extent. Although Toronto is a financial hub, tech start-ups in the vicinity receive less venture capital investments relative to their competitors in other places. Henry echoed this point in her Inc. article, saying that a “shortage in home-grown VCs, however, ultimately makes securing funding beyond the early stages a challenge for Waterloo companies”. Moreover, while the universities in the corridor accounted for 40% of total Canadian R&D spending, according to McKinsey, university spin-offs struggle to get off the ground. McKinsey argues this is due to certain aspects of intellectual property law and university policy in Canada. The universities retain IP ownership, control of technology transfers, and a share of future revenue related to research led or supported by them. Faculty members are offered little flexibility and support when they decide to pursue commercial applications for their research. These factors stunt the growth of start-ups and disincentivise commercial ventures, McKinsey claims.

Other negative factors are cited by McKinsey, and these include: a dearth of executive and managerial talent with “hands-on experience of scaling up companies”; and “poor infrastructure” which hampers connections between concentrations of expertise within the corridor. Problems such as these are not helped by the fact that the area lacks a cohesive socio-economic agenda, fundamentally because there is no formal coordinating body with the power to drive policy change for the Toronto-Waterloo corridor.

Despite these drawbacks, the cities of Markham, Waterloo and the rest have made an outsize contribution to the automotive industry. And perhaps we should not be surprised. After all, those sectors where the Silicon Valley giants already dominate – social media, cloud computing, computer and phone software – are less likely to appeal to start-ups in a fledgling tech hub than are relatively new sectors – autonomous and connected vehicles, for instance – where nobody has established a firm foothold and where they can potentially make a greater impact. The fact that Toronto and Waterloo cannot compete directly with San Jose and Sunnyvale might not, in the end, prove to be a significant disadvantage for the future pioneers of digital automotive technologies. Just as BlackBerry did, the tech industry of the Toronto-Waterloo corridor might elect to focus their attention on next-generation vehicles and leave the smartphones to their rivals.

1 https://blog.waterlooedc.ca/what-is-toronto-waterloo-corridor

2 Formerly of Sunnyvale, California (i.e., in Silicon Valley).